For four months last year, I had the opportunity to live on the islands of Lakshadweep. Imagine, from walking between throngs of people in the shadow of concrete towers, I was transported to a place with turquoise water as far as my eye could see, coconut tree skylines and a handful of people I would get to know by name.

Today, thousands of miles away from that wondrous abode where the sea, the sky and the inhabitants seemed to care for me like I was one of their own – my bond with the islands has only grown stronger.

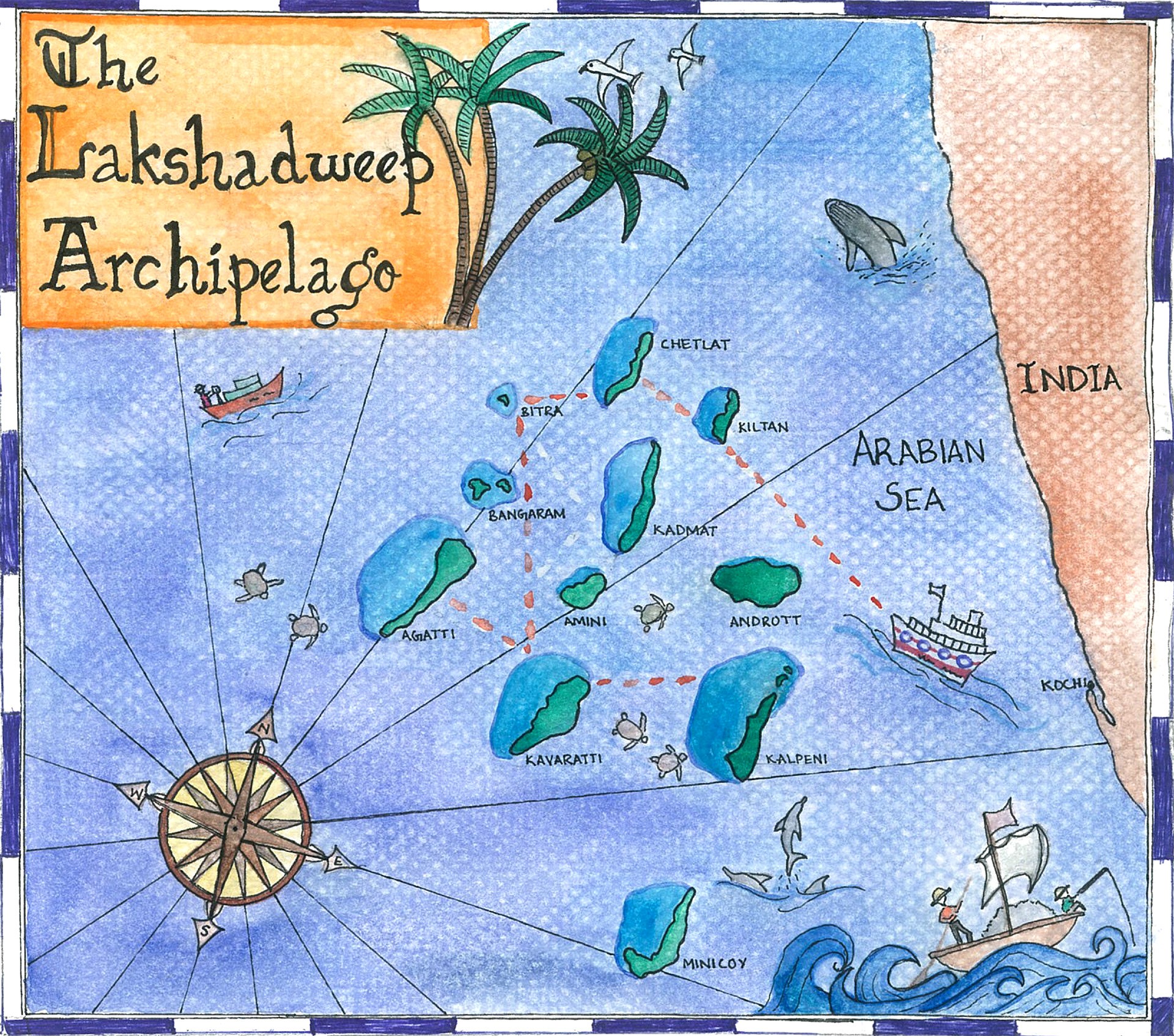

Lakshadweep is India’s smallest union territory, located in the Arabian Sea. It is an archipelago of 36 islands – 12 atolls, three reefs, five submerged banks and ten completely uninhabited islands. Before my time there, I had never been to an island before. I applied for a research permit, and two months later, I boarded a ship from the port of Kochi. It took two days to reach the Agatti and Kalpeni islands, where the population is a mere ten thousand.

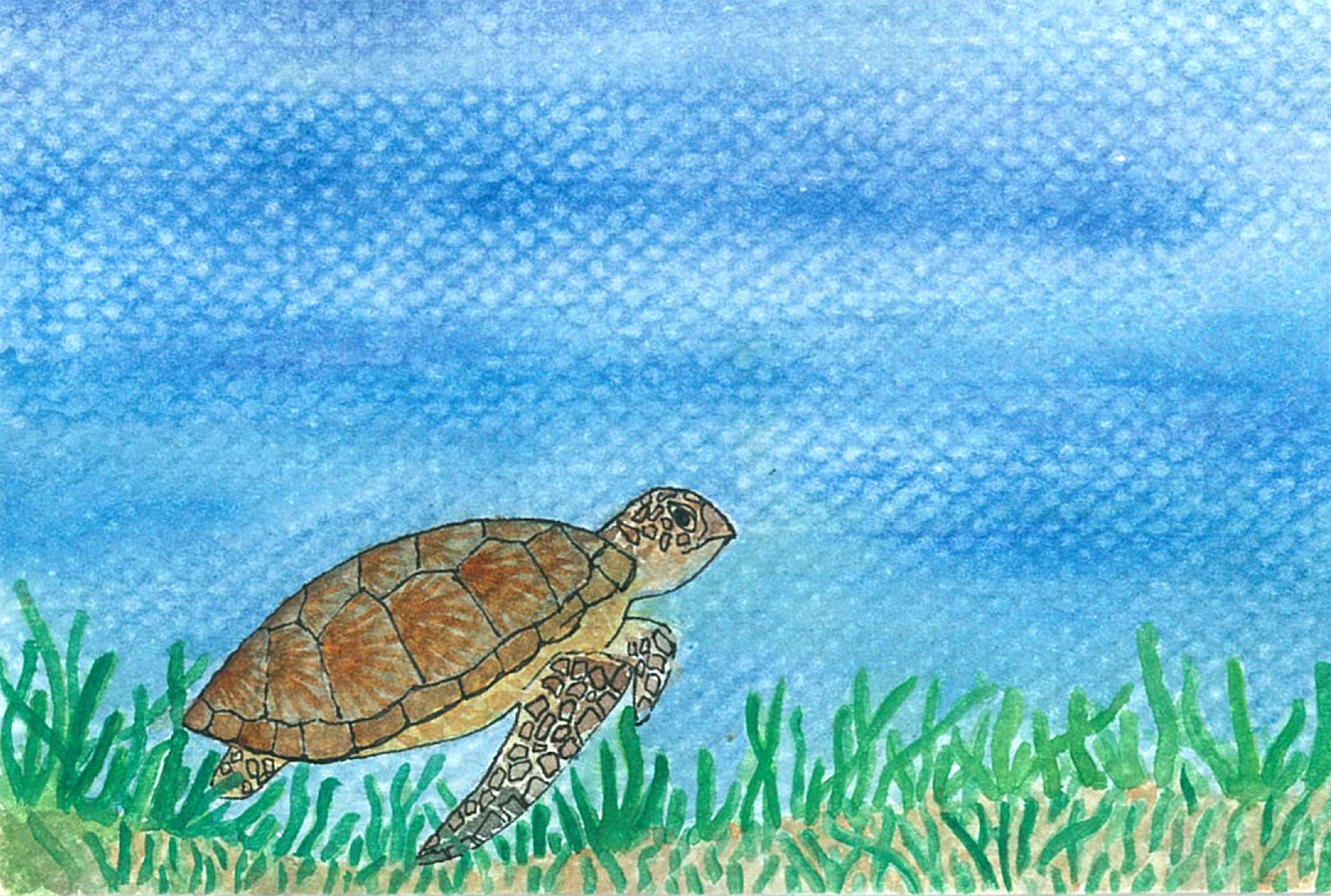

I was there to study the foraging habits of endangered Green Turtles – a species that is relatively under-studied compared to Olive Ridleys and Leatherback Sea Turtle populations in India. Green Turtles are the only herbivorous sea turtles. They feed predominantly on seagrass found in the shallower parts of the sea.

In fact, the region around the Lakshadweep islands supports the largest population of Green Turtles in the Indian subcontinent. But the situation here is quite complex. Fishermen blame the decline in their catch on these foraging turtles. They believe that fish stocks have fallen because the seagrass meadows – which act as fish nurseries – have been overgrazed. This has led to an increase in fisher-turtle conflicts in the recent past.

My focus was on studying how the decline of seagrass in the lagoons would influence the turtles’ diet. I mapped the seagrass distribution across the Agatti and Kalpeni lagoons, and sought to understand how their diets shifted in areas where the seagrass densities were low. An understanding of the Green Turtle foraging ecology is integral to their conservation, because of their endangered status.

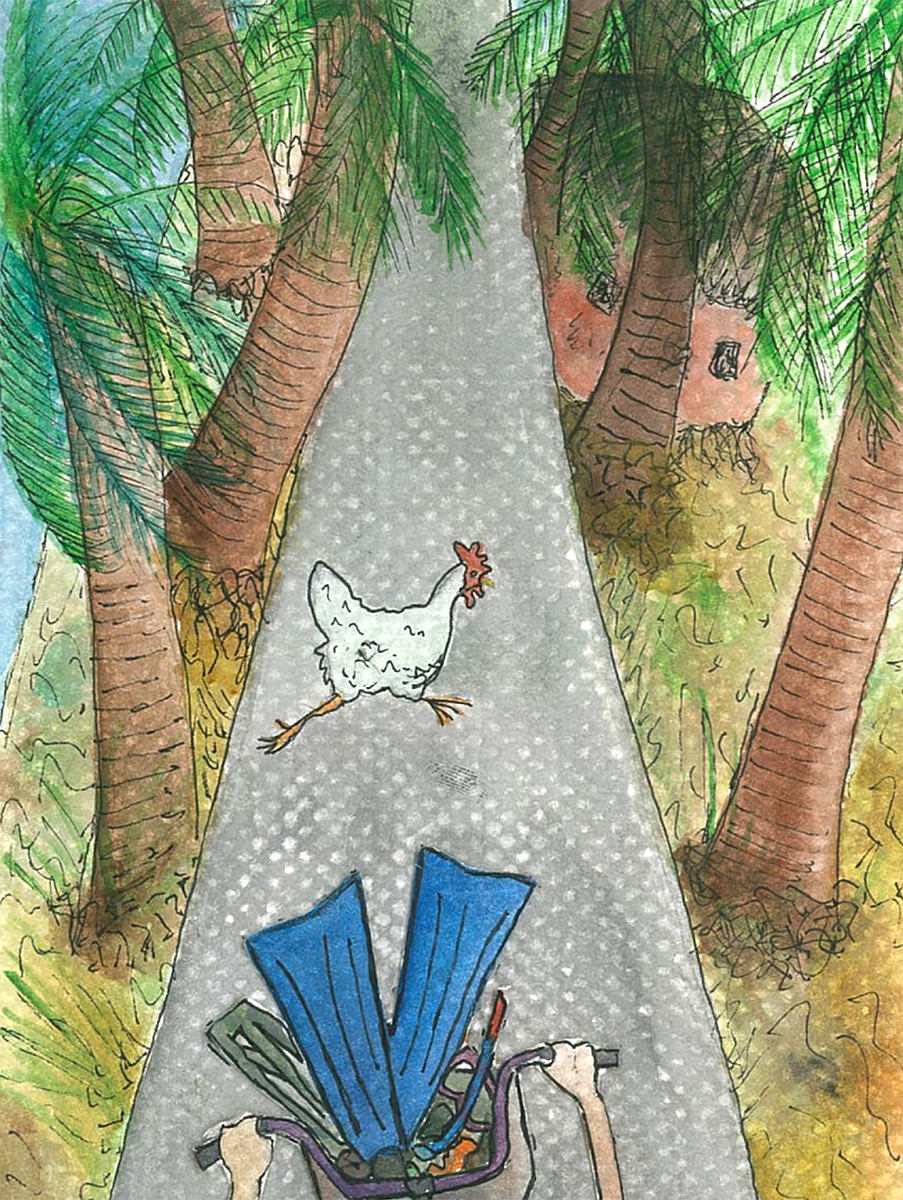

Every day in Lakshadweep, I would wake up early, as it gets uncomfortably hot after sunrise. But for me, it wasn’t only the heat that urged me awake, it was the excitement to get to my ‘office’ and observe foraging Green Turtles over seagrass meadows, busy fish over the reefs, rays flying by and an occasional shark. I would speed down the narrow streets of Agatti on my dilapidated Ladybird cycle, with my research equipment – snorkel, mask, flippers, weights, GoPro, and makeshift writing pad – sticking out of the front basket.

Weaving past bunches of busy hens and galloping goats, I would arrive at Jaffer’s house. Jaffer played the role of friend, boatman, chef and island newspaper. I hired his boat, Nihla Fatima for my work in the lagoons. She was a high-tech, swanky thing, with great speakers (I often heard Coldplay and Dire Straits while Jaffer was cleaning his boat).

My dives involved taking counts of seagrass in the lagoon – quite a challenging task as it involved laying transects and plots all across the lagoon. Each plot would take me a minimum of three hours to finish, as I would “duck dive” to the base of the lagoon to take seagrass counts by laying down small subplots made out of PVC pipes. Despite the rigour and intensity of snorkeling for close to six hours every day, I enjoyed my fieldwork thoroughly.

After I surfaced from my dives, I would have lengthy conversations with the rest of the boat crew – mostly in broken Malayalam, hand signals and my facial expressions – which would leave them endlessly amused. All of them were involved in pole-line tuna fishing, but they would make some forays out on the water for tourists too.

They would lay out a plate of khaddi (assorted snacks) for me after I surfaced from a dive, with fresh lemon juice, kattan chaiya (black tea) or tender coconut water. Sometimes, Jaffer would make delicious fish biryani while I worked underwater. (Although I went there as a vegetarian, I had no choice but to switch to a fish and chicken diet as vegetables, shipped from the mainland, are not very easy to get a hold of. Once, we spotted carrots in the local store after several weeks, but they refused to sell it to us as these were “advance booked carrots”.)

After long days out on the water, I would spend the evenings on the beach, chatting with the women and children, with a cup of kattan chaiya in hand. The women of Lakshadweep are quite reserved and are not allowed to swim in the azure waters that surround them because of their religious beliefs. They were always curious about what I saw underwater, and would imagine the marine wildlife in their backyard through my stories and descriptions. Later, when I was alone, I would reflect on the stories that were exchanged with wonder.

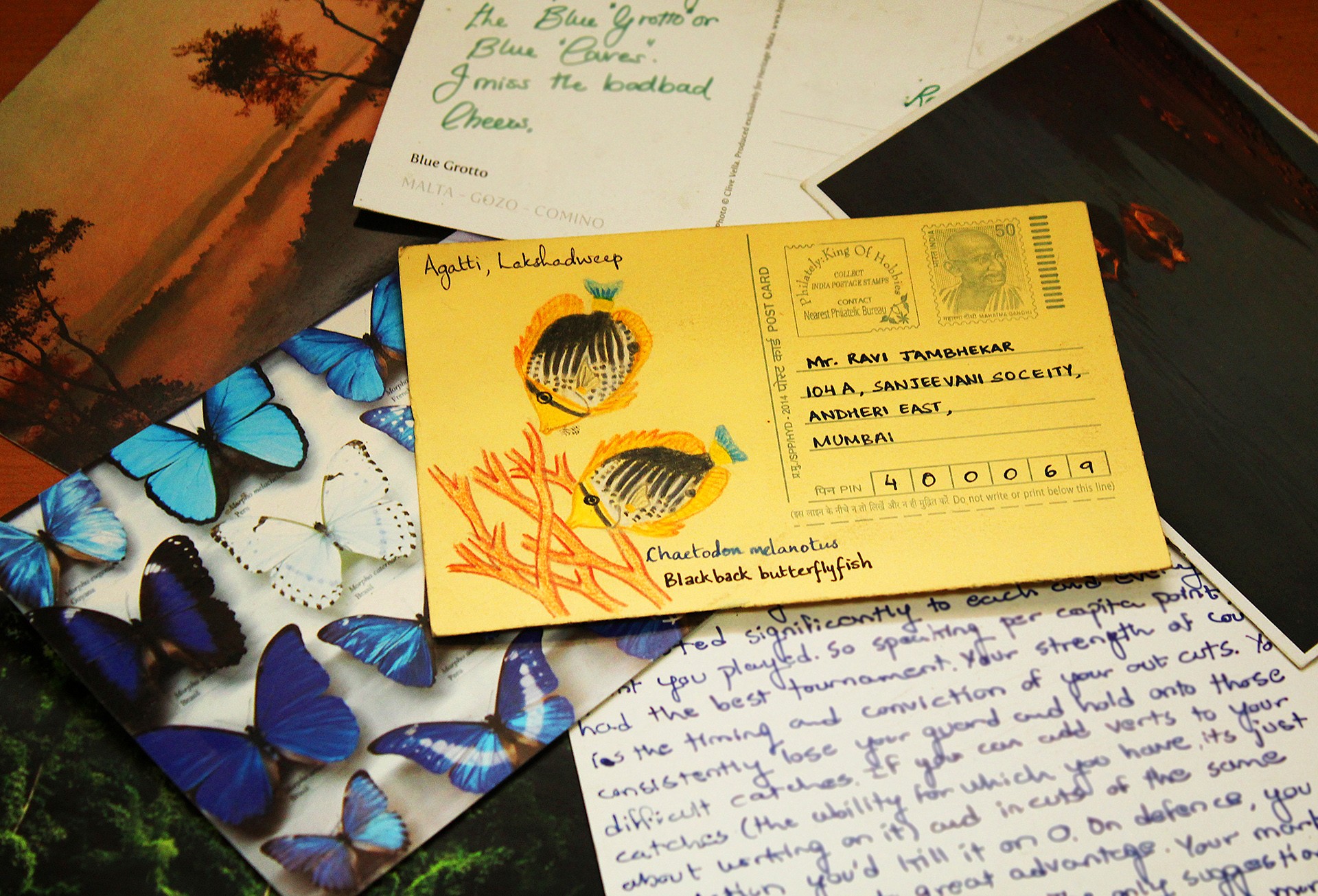

There were so many special moments I wanted to share with my family and friends back at home. But throughout my time on the islands, I had very limited internet and network coverage. I’m not too talented at photography, so I documented whatever I could through art. I decided to make postcards to send to people back home. This way, I would remember the features of the organisms I was seeing or the landscape I was living in vividly.

Each postcard took me around a week to make, because I would usually be exhausted after fieldwork. The first set of postcards never made it to my friends – I was so disappointed. So I decided to write inland letters instead. I sent letters to some friends and my family. Funnily, some of them reached long after I returned from the islands! As for those handmade postcards, I feared losing even more somewhere over the sea, so I handed them over in person, once I got home.

I can easily say that some of my closest friends now, I made in Lakshadweep. Even though I haven’t been back for a year, I still receive messages from the locals to enquire about me and my family. And of course, I still paint, write and dream of Lakshadweep.

To read more about sea turtle and marine conservation projects, visit www.dakshin.org